Of Miss Hilde Holger it may truly be said that she has heard the call of the gods.

– Robert Mangin, Journal des Theatres, Paris 1927

By the time she died in 2001 at the age of 95, Hilde Holger had transformed modern dance, first as a pioneering dancer and choreographer and later as a celebrated dance teacher. As a principal exponent of expressionist dance, she has had a lasting influence on three generations of choreographers and dancers. As an educator, she insisted on the highest standards, waging a constant struggle against uncritical self-glorification, against surrendering to vulgarity. In her art and her teaching she never shied from taking great risks, occasionally scandalizing critics and audiences in the process. But her students adored her. I have never been orthodox in my work and I welcome to my school anyone who is serious and unprejudiced. As a revolutionary her motto was Disorder rules!’ — she championed the use of dance as therapy for the mentally disabled.

Her vision of dance was one of total theater, embracing radical design and movement. A dancer, she contended, must be a technician, an artist and a full human being. No movement could be important if it wasn’t guided by thought and emotion.

With Holger, more than with any other artist, dance is really a prayer, wrote the Parisian theater critic in 1927.

A proud affirmation of identification with every human expression, was how another Viennese critic described her work, adding that her dance was something which partakes of God.

Her dances, critics said, offered audiences an escape — from the ordinary world of the intellect, and from our sad and serious reality. Holger was capable of taking people into the country of the soul of myth and legend and fairy-tale, of color and rhythm, where all our sadness dissolves into rainbow colored clouds And so she populated her ballets with giants and fairy-children in the garden of a happy land witches dancing in the fire and darkness on the Brocken mountain performing their unholy rites crystals and gnomes weaving their rhythms in the caverns of the earth, and the Golem, the terrible elemental of dark power.

Perhaps only a city of such cultural ferment as Vienna between the wars could have produced an innovative artist like Hilde Holger who became both the embodiment of expressionist dance and its passionate advocate. I do not want you to function as a machine, she exhorted her students in Vienna, Bombay and London, the three cities she would call home during the course of her long career. I expect from you heart, brain, imagination and expression in your movements. And humanity human feelings as expressed in the art of Van Gogh, Picasso and Goya Her lesson was taken to heart by three generations of eminent dancers and artists: Lindsay Kemp, Royston Maldoom OBE, Cecilia Abdeen, Jane Asher, Kevin Rotardier, Jeff Henry, Carl Campbell, Wolfgang Stange, Liz Aggis, Claudia Kappenberg, Franka Schuller, Monika Koch, Thomas Kampe, Lilina

Tirone, Carol Brown, Rebecca Skelton, Anna Niman, Jacqueline Waltz and many others. 1 In that sense she was at the same time mentor and muse as well as an artist. Even in her later years, increasingly housebound because of illness, she attracted hundreds of young disciples who flocked to her home like pilgrims. They came to learn from her about dance, of course, but also about life. In her teaching she refused to recognize limits; she treated all students the same regardless of their physical stature, race, social, health, talent or mental ability. In 1968 she became the first choreographer to put young adults and children with severe learning disabilities on stage in a commercial theatre.

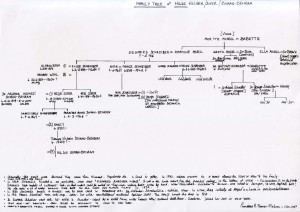

Hilde Holger was born in Vienna in 1905 to a refined, progressive Jewish family. Her grandfather made shoes for Emperor Franz Josef and the Hapsburg aristocracy. Her great grand parents shared a house with Johann Strauss. On her uncle’s side, the family was Catholic. She never had much of an opportunity to know her father who died when she was three. I barely remember him, she wrote, but he left behind some beautiful poetry. I’m sure my sense of artistry comes from him. She was fortunate to be born at a time when Vienna was enjoying an unprecedented cultural flowering. Vienna was a busy and artistic place, she recalled, Sculptors, painters and architects gathered there to swap ideas. And what ideas they were! At the time Holger was growing up Vienna was home to the composers Alban Berg, Anton von Webern, Arnold Schoenberg and Franz Lehar whom she worked with, the painters Oskar Kokoschka, Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, the writer Stephan Zwieg, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and the dancers Greta Weisenthal and sisters, Niddy Innbekoven, Trudi Schoop, Anita Berber, Gertrude Kraus, Cilli Wang and Gertrud Bodenwieser, who would become her teacher, director and friend, and under who Holger danced in Max Reinhardt productions. Holger recalled how in Salzburg, Otto Preminger was the rear end of the idol for the Golden Calf –Tomaselli being the front end. The city had its chronicler in the person of Arthur Schnitzler, who enjoyed posthumous fame with the release of Kubrick’s film Eyes Wide Shut based on his work. But probably no one exerted more influence than the father of psychoanalysis. I knew about Sigmund Freud when he was young, Holger wrote, He was very famous. One of my uncles who worked in a hospital was a great friend of his.

At the age of six, being too young to go to the Academy, she started ballroom dancing lessons with her older sister; ten years later she was touring Europe with the legendary troupe founded by Bodenweiser. According to one story, Bodenwieser called her mother to say that her single-minded teenaged daughter ought to choose another career. Holger wasn’t dissuaded. At the age of 18 she made her solo debut as a performer at the renowned Secession and later Hagenbund in Vienna. She went on to form her own dance group the Hilde Holger Tanzgruppe as well as a children’s dance group. A blue-eyed beauty with blonde hair that flowed to her knees, she became a popular model for several noted photographers including Anton Trcka, Martin Imboden, Hermann Schieberth, Pepa Feldenscharek, Ingret, Felix Braun, and Fred Fehl. Artists Pick-Morino, Felix Harta, Wolfgang Born and Joseph Heu also drew and sculpted her. She had the same mesmerizing effect on critics. Angel face, stern face, Madonna-like, with blond curls, was how one contemporary described her after attending a performance. Bach came out of her torso, an almost pagan connection to the earth swinging and turning on the waves of the music (performing a) soap bubble dance with shimmering colors of the sun and rocks and suspense in the air and rises and flies off. With a high jump it sinks to the ground and the bubble becomes a human being.

She captivated audiences as well — not just the wealthy patrons of the great opera houses and concert halls — but also ordinary Viennese workers. Holger was an internationalist, imbued with the spirit of socialism. Regardless of her audience, she insisted on maintaining the same high standards. Her devotion to truth gives her the courage to avoid cheap effects and movements which would certainly be enthusiastically applauded by an uninitiated audience, observed one reviewer, because she knows that the duty of the true artist, is not to pander slavishly to the demands of the public, but to spare no effort to improve its understanding and taste.

In 1926 Holger formed her own school of dance — The New School for Movement Arts in the baroque Viennese Palais Ratibor. She was attracted not so much by the bright lights (she was already somewhat of a star), as one Viennese dance critic put it, but by the opportunity to teach. It was teaching – for Holger synonymous with innovation – that in fact became her life’s love and work, and for which she will be most keenly remembered. Many of her students went on to achieve fame in their own right including the great mathematician Max Plank, the medical maverick and writer Ivan Ilyitch and the dancer Litz Pisk, who became the movement coach for London’s Royal Shakespeare Company. Throughout this period while developing her unique dance style Holger became one of the foremost figures in Vienna’s flourishing avant-garde.

On March 12, 1938 German troops crossed into Austria, consolidating the union of Austria and Germany under Nazi rule. Two days later Hitler triumphantly paraded through the streets of Vienna. As a Jew, Holger was forbidden to perform or work. In 1939, with the help of a friend, Charles Petrach, she was able to escape the country. Most of Holger’s family was not so lucky. The Nazis murdered extensively many of her relatives, including her own mother, stepfather and sister.

She had no trouble deciding on a country in which to take refuge: Having the choice of going to the United States or to India I chose the latter being a country of attraction to most Western artists, she wrote. India offered an opportunity to absorb new influences into her work. She was particularly struck by the use of hand movements some 300 of them in classical Indian dance which were used to express life and nature in all its variety.

Describing her as one of the foremost contemporary dancers of Central Europe, a Bombay radio commentator alerted his listeners to the arrival of a great new talent. A Bombay newspaper correspondent went further, describing her as a heroine in our midst as brave as any of those who suffer and labor in the city’s wartime road gangs. I call her courageous because she has remained true to the service of her art under circumstances that would have ruined or corrupted a saint. Bombay society embraced her; after giving her first performance at the Taj Mahal Hotel she received an invitation from the Nawab of Bhophal who asked her to perform solo in the garden of his summer palace where she danced bathed in the light of a thousand candles. Holger wasn’t interested in basking in the adulation of Bombay’s elite; she was determined to open a dance school and do it on her own terms even though it would mean defying tradition. The word ‘professional’ had, till the last years, the same meaning as ‘prostitution’ and dancers here felt ashamed to be called professional, she noted in an article for the periodical Dance. She resolved to change that perception. Against the greatest prejudice, ignorance and lack of background for Western art, I had to start my work and bring greater understanding and appreciation of Western art to the east. In 1941 she opened her school to students of all races, religions and nationalities: Hindus, Muslims, Parsees, Chinese, Swiss, British and Americans. Like Isadora Duncan, whom she revered, Holger taught her students that it wasn’t enough simply to learn movement or harmony if the mind wasn’t trained as well.

Just as in Vienna, Holger became a part of a thriving art community. She befriended the world famous Indian dancers, Ram Gopal and Uday Shankar, who are credited with westernizing Indian dance. Ram Gopal even taught in her studio. Russian artist Magda Nachman, became her close friend and collaborator.

In 1940 Holger met Dr. A.K. Boman-Behram (Adi) a prominent Bombay homeopath and art-lover, who would shortly become her husband. The marriage made Holger a part of an aristocratic Parsee family who had provided Bombay with many of its most important officials and politicians.

In 1946 their first child, Primavera, was born. Two years later, Holger was once again uprooted by war as the subcontinent was wracked by sectarian violence between Hindus and Muslims. In 1948 Holger, Adi and their young daughter left for England.

If in Vienna she was best known as a dancer and choreographer, and in India she achieved prominence as a teacher, in London she acquired a reputation as a pedagogue, movement therapist, and mentor for many aspiring artists and dancers.

Within months of her arrival in London Holger was already performing with her new group in parks and theaters. Picking up where she’d left off in Bombay, Holger opened a new school — the Hilde Holger School of Contemporary Dance. But her philosophy of teaching hadn’t changed. Body and mind constitute a unity, she asserted, for intellectual or mechanical ability alone would fail to produce a dancer. It has often been the case that not only crippled toes, but crippled minds disastrously influenced young dancers and prevented them from becoming dancers. Emphasis on technique risked turning children into mass-produced dancers with no passion, artistry or soul. It was far more rewarding, she wrote, to foster their dramatic and musical senses while their minds are still young and impressionable rather than force their unformed bodies to reach the technical perfection of a stage dancer. She recognized that there were inevitably going to be far more mediocre pupils than gifted ones, so that it was incumbent on a teacher to impart to all students an artistic background which will be useful for any branch of art she may later wish to take up.

Holger’s London breakthrough came in 1951 with the premier of “Under the Sea,” inspired by Camille Saint-Saens’ composition. Even at the risk of stirring controversy she presented the piece in the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields where she’d turned the altar steps into a stage. It was an unprecedented use of a church as theater space. Holger characteristically brushed aside the heated debate she’d triggered. ‘Sea’ was only the first of many performances she put on in a church. Even more controversial was the ballet Adam and Eve which was staged on the altar of St. Phillips Church in Battersea.

Her work was strongly influenced by the cities and countries where she performed and taught; “Rock Paintings” (1975) drew upon the artistic and cultural influences of London while “Apsaras” (1983) was an exploration of her experiences in India. In the summer of 1983 she returned to Bombay the only visit since she left in 1948 — to choreograph for a large dance company directed by Uday Shankar’s cousin, Sachin Shanker. Vienna, though, was never far from her thoughts or her heart. The critics were as captivated in London as they had been in Bombay and Vienna. Writing of a 1988 performance, a Dance Theater Magazine reporter wrote: It was astonishing; achingly simple, inspiring, original and contemporary yet soaked in history.

Holger’s influence also made itself felt in the close collaborations she enjoyed with such composers and musicians as John Beckett, Thomas McLlelland-Young, Roger Cutts, and David Sutton-Anderson, who created original compositions for her performances and dance classes. One of her longer pieces Die Stadt was the result of a collaboration with the Nobel laureate Elias Canneti and the Viennese composer Marcel Rubin. In creating another long ballet After the Flood, she worked with the prominent Chinese author Rewi Alley, and composers Yin Chang-Tsung and William Langford. Her final collaborative with David Sutton was a tribute to her former teacher and mentor in the form of a reconstruction of Gertrude Bodenwieser’s Rhythm of the Unconscious Mind, based on Freud’s writings, which she directed at the Saddlers Wells Theatre a year before her death.

Holger was especially proud of her work with the mentally disabled. Her motives were deeply personal. In 1949, she gave birth to a son, Darius, who had Down syndrome in addition to a severe heart defect and wet lungs. With the same resolve and perseverance that characterized all endeavors she undertook, Holger methodically set about the healing and rehabilitation of her son. She created a form of dance therapy which children like Darius could benefit from. When she told her students, I expect from you heart, brain, imagination and expression in your movements she was as good as her word. Dance was open to everyone who was sincere about it — even students whose brains were impaired by accident of birth. Always the pioneer, Holger became the first choreographer to put on a public performance featuring young adults with severe learning disabilities — the 1969 “Towards the Light,” with music by Edward Grieg, at Saddlers Wells,

Her work with downs and the mentally disabled has been carried on by her former pupil Wolfgang Stange whose AMICI Dance Theatre Company integrates mentally and physically impaired dancers with professionals in its performances. Hilde taught me to recognize and value honesty on stage, Stange has said. In 1996, in honor of Stange’s mentor, the AMICI presented the dance piece Hilde at the Riverside Theatre in London and again in 1998 at the Odeon Theatre in Vienna, for which film director, Steven Spielberg contributed funding. The ballet master of the Viennese Stadt Opera Ballett was so impressed by the performance at the Odeon that a couple of years later he presented performances with young people with severe learning disabilities on the stage of the Viennese opera house that was received with great acclaim.

Holger’s legacy was also honored by her daughter Primavera Boman- Behram who, in addition to becoming a dancer and choreographer in her own right, continued working creatively as a sculptor and fine jewelry designer in New York. From her dancing and teaching experience Primavera developed a corrective system of exercise called Alignment Therapy that helps dances and others crippled by postural misalignment.

In 1998 Holger was awarded the highest honors as an artist from the city of Vienna. (In 2001 she received a posthumous award which was presented to her two children by the Austrian ambassador in London, on behalf of the Austrian government.)

Until her final weeks, Holger was still holding classes in her Camden Town basement studio where she’d lived and worked for more than fifty years. One of her former students recalled an encounter with Holger in her final days: Occasionally she would dance for us, sitting in her chair, her head, shoulders, hands and fingers perfectly in tune with the theme of the day: the plight of whales, Schiele and Schlemmar’s art, chickens, marionettes, the flight of birds.

Hilde Holger wasn’t interested in propounding a particular form of dance so much as advancing an appreciation for the value of dance so long as it subscribed to the highest standards of the art. I believe that there is a room for us all; she wrote, for those of us who admire traditional ballet and for those who are more interested in the modern approach to dance.

Hilde Holger’s legacy will endure so long as we continue to make certain that there will always be room for us all.

Written by Leslie Alan Horvitz, New York, 2005