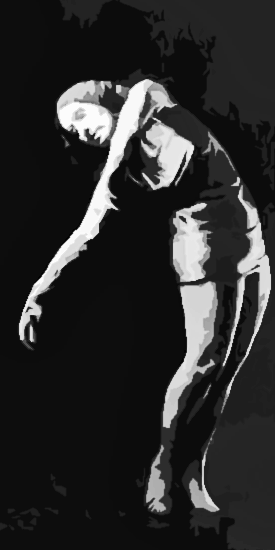

Wherever Holger performed and taught – in Vienna, Bombay and London – she emphasized the need for self-expression; no one could be considered an artist by a mastery of technique alone, she said; passion, heart, imagination and humanity were equally necessary. Uprooted twice by war and political turmoil – the first time from Vienna in 1939, the second time from Bombay almost ten years later as the subcontinent was engulfed by violence between Hindus and Moslems – she offers us an example of the artist unbowed by setbacks or calamity. Her resolve never wavered in spite of all obstacles that would have discouraged many others. Forbidden to dance or teach in Vienna because she was a Jew, she went on to found a school in Bombay that opened its doors to students of all races, religions and nationalities. Recognizing that most of her students would never become professional dancers, she nonetheless believed that they could all benefit from dance instruction. True to that belief, she encouraged the learning disabled to join her classes and perform in commercial venues. She never allowed her vision to be threatened even if it meant defying convention or causing controversy; in London, for instance, she became the first choreographer to use churches as a theatre. Her legacy has been carried out by scores of extraordinary dancers, choreographers and artists who either trained or collaborated with her.

When a Bombay newspaper critic hailed Hilde Holger as “a hero,” he wasn’t exaggerating if a hero means an individual who has the courage to maintain her vision of art and humanity without compromising or surrendering to the temptation of despair. At a time of uncertainty like ours, where the role of art in society is fiercely debated and cultural standards are under fire as never before, it is to creators – and heroes — like Holger that we need to look for inspiration to.